The MkIV hinge has nothing to do with the butt; it's located about eighteen inches above the ferrule on the top joint where the taper (rate of change) is slowest. Perhaps an explanation of how a taper works is needed; forgive me if this is obvious, but it would appear it's not clear to everyone:Nobby wrote:John at Chapmans once told me that the first Mark IVs built by Walker did indeed have a wooden dowel handle and I wonder if the transition from wood to cane was the fabled 'hinge' that some rod builders speak of? Unless they are talking of the change in taper?

A compound taper was hardly a new thing though...the Wizard has a swift change in taper for a few inches, swiftly 'corrected' by another change to bring everything back as though there had been no compound taper at all.

Does flex in the handle help casting? Milwards thought so....enough to patent their reverse tapered butt.

If you take a section of rod - whether wood, steel or split cane - that has a constant diameter (i.e. no taper at all) and apply a load to one end with the other held firm in the manner of a cantilever beam, the shape of the resulting curve will not be constant, as the biggest bending moment will occur towards the fixed end. This is how a fishing rod functions, and all subsequent design considerations must be based upon the load being applied to the free end. Now, as the load increases, the rod deflects in proportion to the distance (length) from the fixed point. Furthermore, the deflection is proportional to the fourth power of the length, so a rod twice as long deflects sixteen times as much for any given load, assuming the same diameter in each case. The load transferred along the rod (or beam) is not constant however, as for every inch (or foot, or metre, or whatever increment you choose) back from the point of loading, the stress increases by a factor proportional to the distance from the extreme end. In other words, the stress becomes greater the nearer to the fixed point you get. This is why the curve of a level diameter rod is greater at the butt than the tip.

In order to create a rod which bends into a constant curve, the rod must increase in diameter by a certain amount for each increment of length - in other words, it must be tapered. The rate of taper can be established mathematically so that the stress at any point remains constant - Everett Garrison's book 'A Masters Guide To Building A Bamboo Fly Rod' goes into the maths of it in detail, even to the extent of accounting for the load upon the tip generated by line, rings, whippings and varnish. After all, a point three inches from the tip has a transferred load of X (this being the notional design load) plus the tip ring, plus three inches of rod, wheras a point sixty inches will have a transferred load of X plus sixty inches of cane plus maybe eight rings.

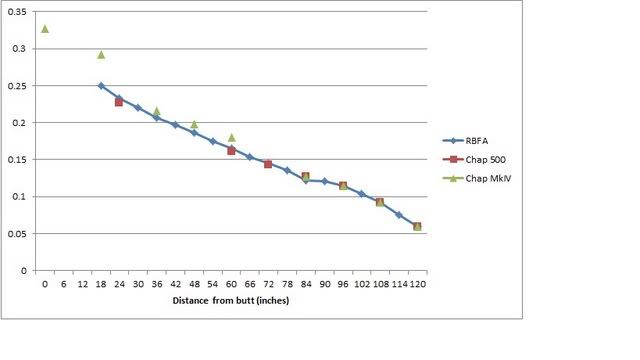

Anyway, if we accept that a rod must have a taper to prevent the load (stress) being greater at the butt than the tip, what happens if that taper is varied? Take an easy one first; suppose you make it with a faster taper than is needed to maintain an even radius to the curve. This results in a rod which exhibits a stress curve resembling a parabola rather than an arc. Both examples so far have what is termed a 'straight taper' - the rate of change per foot run is constant. If you vary the rate of change along the rod's length you get a 'compound taper', and most of the best rod designs incorporate a compound taper of some kind, to fulfil a specific design function. The design of the MkIV started with the basic taper needed to maintain an even stress curve - an arc. The taper was then increased (made faster) in the lower half to stiffen that part up a bit, as a rod with a taper that gives it a perfect quarter circle arc will, if loaded further, feel weak at the butt as the load transfers towards the fixed point (your hand). This point is important, as will become clear in a minute. The taper at the tip was also increased to make the tip finer than needed for a perfect arc; this made the rod better for casting light baits. Finally, the extreme butt end was made much stiffer with beech dowell or whole cane under the corks, to create a powerful lever for casting - quite the opposite to the Milwards 'versa' designs, which were developed to give more spring in the butt. More of those in a moment.

So what of this 'hinge'? Well, the MkIV taper has a fast taper tip (top two feet) followed by a slower taper to give a perfect arc stress curve, followed by a faster taper to provide controlling power lower down, and stiff butt for casting. The hinge occurs in the middle of the slow taper section - eighteen inches above the ferrule. Remember how the 'perfect arc' taper feels weak at the butt if loaded beyond a certain point? This is what happens when the whole rod is flexed, as in casting. The rod wants to bend more in the slow taper section; the weight of the cane above the hinge throws the load back down the rod, but the steeper taper below resists deflection, forcing some of the load back up the rod. The outcome is that the greatest flex occurs midway along the slower tapered part. It might seem odd to make a rod have to deal with a localised stress, but in fact the stress limits of split cane are far in excess of those generated in normal use - though if you try to cast a pound of lead with MkIV you'll probably break it - and ten to one the break will occur at the hinge unless the rod has a hidden weakness somewhere else (badly fitted ferrules for instance). Moreover, the hinge helps with casting and striking; the effect in both cases is to slow down recovery from deflection just enough to create a kind of secondary impetus, adding energy to the cast one the one hand, and helping to set the hook firmly on the other.

Some people think a hinge is created by having a reverse taper at a specified point, but it is not so. If you did make a rod like that, it would be strained beyond its limits as soon as you flexed it, and would break soon after. The only place for a reverse taper is at the extreme butt of a rod which is designed to be held at a point above the start of the reverse taper. It is there to provide some flex in the butt when casting two-handed, and in general use is not subjected to any load at all.